Anna C. Verna Playground at Philadelphia’s FDR Park has the largest swing set in North America. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

New parks in Philadelphia, Memphis and Tulsa show that the key to making playgrounds fun for all ages is designing them for teenagers

A swing can be the simplest thing: two chains attached to a board, a rope knotted through a disc, a chair suspended from above. Swings appear on ancient Greek vases as instruments of leisure, and in eighteenth century Thailand as vehicles for competition.

That’s the thing about swings: They can be sociable, but they are also physical. This inviting duality has often been undermined by public safety standards, which discourage swings for more than one person and mandate that they be far apart. After a certain age, swinging solo loses its thrill.

But at Anna C. Verna Playground at Philadelphia’s FDR Park, on the south side of the city, the largest swing set in North America was designed to test those limits. Not by creating unsafe play, but by transforming those standards into something challenging, unusual, beautiful and rewarding for swingers of all ages. The playground, which opened in October and was designed by WRT Design with Studio Ludo as play consultant, features two acres of nature-based play, including seven slides of increasing height and speed, two steel-and-rope “birdhouses” ascended by climbing nets, three log climbers, and assorted shady picnic tables, rock circles and sittable logs.

Custom-designed “birdhouse” structures with slides and climbing areas at the Anna C. Verna Playground. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

A 20-swing structure for visitors of all ages at the Anna C. Verna playground. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

The centerpiece, however, is the 120-by-100-foot elliptical “megaswing” from which 20 different swings of five different types hang in invitation to all the users of the park—from homeschool moms to tailgating Eagles fans, teenagers on a half-day to grandparents with toddlers, all of whom can train, bus, cycle or drive to the park.

“We are social animals, and play fosters social relationships,” says landscape architect Meghan Talarowski, executive director of Studio Ludo, who is also a certified playground safety inspector. “This park is 15 minutes from my house, and since it opened, it has been completely packed.”

At a time when many cities and business owners seem to want nothing to do with teenagers, it is refreshing to see a brand new public space issue them an invitation—and to go there and see that happening. Toronto urbanist Gil Penelosa, founder of 8 80 Cities, has long argued that designing a city that works for eight-year-olds and 80-year olds is a city that works for everyone. Watching the kids, teens, parents, grandparents and even the Eagles fans at FDR Park made me want to write a new motto: If you make a playground that is fun for teens, it will be fun for everyone. That fun starts with the swing.

“If the teens like it, it must be good,” Talarowski says.

Salyut Playground in Gorky Park features a 29-swing structure in Moscow. Photographer: Natalia Minovalova/Shutterstock; Video: Shutterstock

On the other side of the globe, along the Moskva River that runs through central Moscow, stands Gorky Park, that city’s great central park. In 2018, Gorky Park celebrated its 90th birthday with the opening of Salyut Playground, a collaboration between the park administration and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. The centerpiece of the playground’s sprawling design is the other Mega Swing, a 141-foot-wide tilted ellipse, supporting 29 swings and lit at night with multicolor LEDs. The Russian swing was designed in collaboration with Richter Spielgerate, the German manufacturer behind much of the equipment in the US’s most ambitious parks.

Talarowski had been enamored of the Moscow swing since she first spotted it doing online research. (Pro tip: Do not Google “adult swings.”) She got her shot at the Anna C. Verna Playground in Philly, where she nestled a smaller ellipse—still equivalent to the size of a baseball infield—into FDR Park’s existing lagoon, like the thrust stage in a Shakespearean theater.

“There was this natural curve in the lagoon, and we were trying to connect the play design to the site conditions, without taking down any trees,” says Allison Schapker, chief operations and projects officer for the Fairmount Park Conservancy, which is working with Philadelphia Parks & Recreation on the multi-phase, climate-sensitive $250 million dollar FDR Park Plan. “This is the point, if you are swinging high, you get views back to center city Philadelphia, so we are connected with both nature and the city.”

There are bucket-shaped rubber baby swings and single-plank swings. There are true basket swings, big enough to lay back and watch the migrating geese or sit crisscross applesauce and chat with a friend. There are those adaptive swings, as heavy as a tank, and there are the so-called “VIP Swings” that work like an overhead see-saw.

The swings hanging around the ellipse are carefully chosen to suit all ages and abilities. They’re also made to let kids go head to head. “It’s circular, so you are looking at each other as you swing, and you are interacting with folks watching in the middle. Many of the swings are designed to be collaborative or collective. And even the ones that aren’t” — Schapker trails off, interrupted in her soundbite by a group of teens piling on to one of the heavy, lounge-like inclusive swings — “people find a way.”

While it was originally designed by John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., FDR Park developed its reputation among teens starting in 1994, when the city sanctioned a skatepark built up informally by skaters. More recently, the leaders of that park were part of the community engagement process for the park master plan. But not all teens love to skate or play organized sports, and both activities have traditionally been male-dominated. Swings, shady seating areas and teen-scaled play equipment are all ways to make outdoor activities have broader appeal.

While the megaswing pushes the limits of regulation, it still bows to them. Safety standards cap swing heights at 16 feet and draw an imaginary rectangle around the swing’s arc on the ground. This ensures sufficient padding, should you fall from that height, as well as safe passage around the swinger for people on the ground. The result is that the Philadelphia swing looks a little underpopulated: imagine the rectangles around each swing angled in a curve, creating lots of wedges of empty space. When everything’s in motion, you might not notice, but the swing-as-sculpture has a forlorn aspect.

The Anna C. Verna Playground is phase one in the restoration of FDR Park; the master plan is also by WRT. As part of their commitment to keeping things natural, WRT specified very little paint and plastic: The slides and climbing structures are stainless steel and rope, much of the seating is rocks and logs, the swings themselves are black plastic, plus more metal and rope. The big swing and the playground’s other custom pieces were designed in collaboration with equipment manufacturer Berliner Seilfabrik. Underfoot, the springy safety surface is not the flip-flop colored rubber of most playgrounds, or high-maintenance and inaccessible woodchips, but a permeable and recyclable cork product that comes in a subtle, toasted brown. “We feel strongly playgrounds should be sophisticated,” says Talarowski.

Sophistication isn’t just picking fall colors rather than primaries: It signals to users that this equipment isn’t just for kids. As part of their two-year community process, the conservancy “did engagement activities on site with kids and their families,” says Schapker. “Overwhelmingly, across every age group, they said they wanted to swing.”

The climbing structures are made of stainless steel and rope at the Anna C. Verna Playground. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

The safety surface is made of a permeable and recyclable cork product at the Anna C. Verna Playground. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

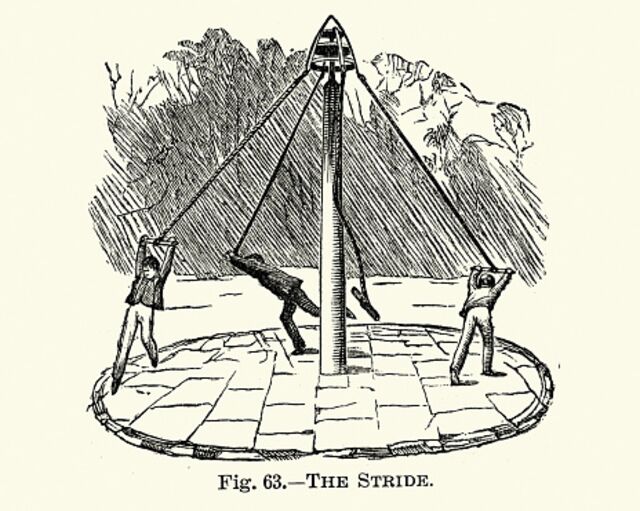

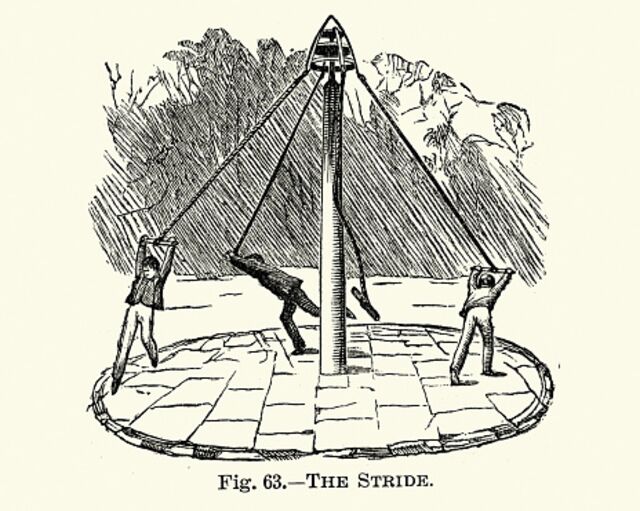

Big swings dominated the playgrounds of the early 20th century: pipe-rail constructions that stood several stories high, with board seats dangling on long chains. The fours Ss — swings, slides, see-saws and sandboxes—soon became the standard template for urban playgrounds in reform-minded cities. The aesthetic was minimal and hard-wearing, steel with wood parts where necessary, made to pack the maximum number of play spots into a minimal, dirt-floored footprint. Innovation flourished even within these narrow parameters. The jungle gym, the merry-go-round and, most notably, the giant stride, would emerge from the Progressive Era as patented designs, manufactured and distributed across the country.

Patented in 1926, the giant stride was a pole with a circular mount on top, from which ladders of chain with steel cross pieces were hung. Kids would grab those handles and run — or stride—in a circle, gaining enough momentum to swing through the air. If they were going fast enough, they might get tossed off into the grass verge. The armchair playground expert of today sees so many problems: climbing hazard, inadequate fall zone, potential for spraining ankles or dislocating shoulders. But these swings were also collaborative, developmental and a heck of a lot of fun. As I watched four teenagers pile on to the adaptive swing at Anna C. Verna Playground and really get that thing going, I caught a glimpse of that anarchic 1920s energy.

A vintage illustration of children playing on a giant stride in the 19th century. Source: Duncan1890/Getty Images

The structure and silhouette of those big swings by industrial manufacturers also caught the attention of artists: As Isamu Noguchi began exploring the idea of playground-as-sculpture in the 1930s, his models, prototypes and eventual built parks incorporated the swing. A 1939 miniature of play equipment for Ala Moana Park in Honolulu (never built), includes a three-swing set shaped like a right triangle, the seats hanging from a bent-steel header that steps down with the slope of the triangle. Contemporary photographs are harshly lit so that the swings’ long chains stretch even further as shadows on the ground. When Playscapes in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park was built for the bicentennial, those triangular swings were part of the landscape.

Noguchi’s only playground in the US, Playscapes was restored in 2008. Much of the Japanese American designer’s custom equipment was grandfathered in, but the swings required some modifications to meet post-1970s regulations. The highest swing was removed, the other swings’ chains were shortened and more-protective toddler bucket seats were installed. Nonetheless, Noguchi’s original goal, “to bring art into daily life,” remains in effect, says Robert Witherspoon, program manager for public art for the City of Atlanta. “There is not a ‘how to’ manual for this play equipment,” he adds. “Everyone who visits the Playscape is exposed to design elements, art and vibrant color.”

More recent ambitious parks have also embraced big swings, often as part of a larger conversation about risky play. At Gathering Place, the 66.5-acre Arkansas River-front park that opened in Tulsa in 2018, “we used the tallest swing allowed by code, which is 16 feet tall,” says Scott Streeb, principal and director of the Denver office at Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA). At the Port Lands in Toronto, the firm plans to use the “To and Fro Swing” – another see-saw-like contraption – “as part of an agility course that includes cableways and other swinging elements.” His current favorite is a caregiver swing, with a flat seat for the parent and a bucket for the child, which allows a pair to swing in tandem, maintaining eye contact. “I’ve seen many parents mind-numbingly bored pushing a kid in a swing on a playground,” Streeb says. “We used it in a park in Fort Collins, [Colorado], and there is a line around the swing set for it.”

Streeb sees these swing variations as simultaneously supporting social and physical skills. “When there are elements that it is not entirely obvious how to use them, and you need to figure it out, that’s a place to show off problem-solving skills,” he says. “For that adolescent age group, parents are less important and developing relationships with friends is more important. You are thinking about the teamwork aspect.” Plus, he adds, “The cableway [a.k.a. zip line] at Gathering Place is the most popular. You will see adults go down that all day.”

The Thursday I visited FDR Park was a half-day for Philadelphia public schools, and all of the constituencies Talarowski and Schapker were telling me about made an appearance, as if scripted. A group of five 16-year-olds had picked up food and taken public transit to FDR Park to eat lunch, hang out, and play, climbing on, in, and over both the swings and the slides. They told me they had spotted the playground while watching futbol in the park over the weekend and had been back a handful of times since. They were delighted to hear that phase two of the park plan included the adaptive reuse of a 1919 stable into a Welcome Center (also by WRT), which will provide hot food, restrooms and covered gathering space starting in April.

The Anna C. Verna Playground was designed for both children and adults in mind, offering a welcoming space for all. Photographer: Caroline Gutman/Bloomberg

A group of homeschool kids aged 3 to 14, having visited the neighboring American Swedish Historical Museum, fanned out across the equipment, all easily in sight of their chatting moms. And a couple of grandparents, minding three under-10s, gave their suburban grandchildren a thrill with a visit to a new-to-them playground. “We always try to take them someplace outside,” said the grandmother. “This is so much better than anything near where they live. I just hope they take care of it.”

Watching people encounter new swings for the first time, and figure out how to use them, was like watching improv. “When we were designing these, I did not get them,” says Schapker, gesturing at the VIP swings. “But those are the swings you find people waiting on line for on the weekends. When I was here with my niece there was a little boy about her size on one side of it. He was stuck. I said, ‘Why don’t you go sit on the other side, see how it works?’ And they played together for about 15 minutes.”

On my afternoon trip there was no one for me to befriend. Sitting at one of the picnic tables in the sun, however, I watched as a couple in their 20s stopped, stared, and eventually see-sawed back and forth with great hilarity before breaking off to smooch. Such is the romance of swings.