[ad_1]

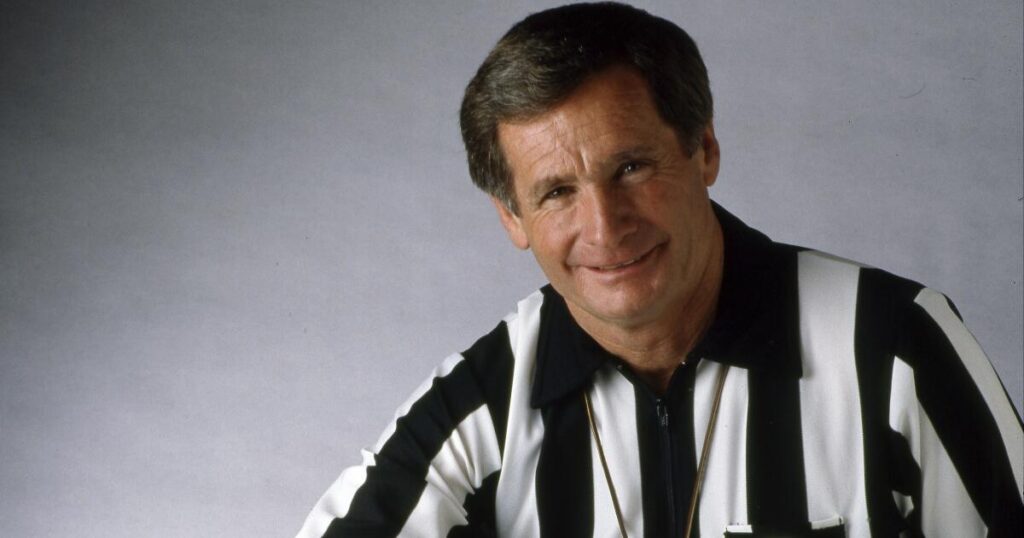

It’s the aim of NFL officials to essentially go unnoticed. When a game is over, they want fans and pundits to be talking about the action on the field, not the people in stripes and whistles.

Jim Tunney and Al Jury lived — and thrived — by those standards.

The two giants of their profession died recently, and the absence of the two Southern Californians is deeply felt in the officiating world.

Tunney, who at 95 was the oldest living retired referee, died Thursday at his home in Pebble Beach, Calif. He had been the NFL’s youngest game official when he was hired as a 30-year-old field judge in 1960 and in the ensuing decades was in stripes for some of the most memorable games in league history.

Jury died at 83 in San Bernardino, his hometown, and was regarded as one of the NFL’s premier downfield officials. He worked a record-tying five Super Bowls and almost certainly would have been on the field for more had he not suffered a career-ending broken leg during a game in 2003.

When he wasn’t officiating games, Jury was first a mailman and later an officer for the California Highway Patrol. On the field, he wore thick protective goggles and was beloved by his fellow officials.

“Not only was he great mechanically, but he had uncanny judgment on the field,” retired NFL referee Mike Carey said. “The league isn’t black and white, so knowing what to call is really important. Both Al Jury and Jim Tunney were great at not only demonstrating it but at sharing that wealth with new officials coming in.”

Tunney, a graduate of Occidental College, had a day-to-day job as principal of Fairfax High in Los Angeles for seven years.

“School was out on Friday afternoon, and the next morning I’d get on a plane at LAX and fly to Detroit or Green Bay or Miami or someplace else by myself,” he told the Los Angeles Times earlier this year. “First-class travel thanks to [then NFL Commissioner] Pete Rozelle.”

The self-effacing Tunney wasn’t incognito to a lot of his students.

“Particularly at Fairfax because those kids were so sharp,” he said. “They’d come back on Monday morning and say, `Oh, you sure screwed up that play…’ I’d just laugh and say, ‘Yeah, I probably did.’”

Among the iconic games Tunney worked were the “Ice Bowl,” a frigid classic between Dallas and Green Bay; “The Catch,” when Joe Montana’s pass to Dwight Clark toppled the Cowboys and sent the San Francisco 49ers to their first Super Bowl; and “The Fumble,” when Denver beat Cleveland in the AFC championship game. He refereed three Super Bowls.

When the NFL would use an illustration of which gesture was used for a specific call, the league used a drawing of Tunney.

CBS play-by-play announcer Jim Nantz put it succinctly: “In the world of officiating, Jim Tunney is Babe Ruth.”

Jury started officiating high school games at 18 after graduating from Pacific High in San Bernardino, where he was a multi-sport athlete. He began his NFL career in 1978 when, as passing games were becoming more sophisticated, the league expanded officiating crews from six to seven.

“The most difficult call in the game is pass interference or offensive pass interference, that contest for the ball,” Carey said. “It’s a completely different art and science that you have to devote a lot of time, not just to the rules, what you can or can’t do, but learning the nuances of what receivers and defenders do.

“You have to watch all four appendages and the ball the whole time. It’s a real skill set and Al mastered that and helped teach that.”

Jury was selected to officiate Super Bowls between Chicago and New England (1985 season), Washington and Denver (1987), San Francisco and Denver (1989), Dallas and Buffalo (1993) and St. Louis and Tennessee (1999).

“Referees tend to get all the attention, but Al Jury was as good at his job as any referee was good at his,” said Mike Pereira, Fox rules analyst. “He was the go-to guy for any tough game that you had. Nobody challenged that man. He didn’t take any guff — that was the CHP in him — and he was just a great guy.”

[ad_2]

Source link